"an exchange of good gifts between strangers"

Posted on March 22nd, 2015

Tassos Stevens writes: I was invited by Annie Rigby of Unfolding Theatre and Kylie Lloyd of Northern Stage to deliver a provocation in a symposium recently on participatory art and the question – how does this work impact and benefit the artists involved? I spoke alongside Annie herself and Matt Peacock of Streetwise Opera. Here’s what I spoke. It was a fine event to kick off a developing relationship between Coney and Northern Stage.

Hello, thanks for being here. I’m one of Coney. We make participatory theatre which has you the audience at its heart, where it is up to you how you choose to play. Or – we make play with an ethos best summed up by three key principles – a principle of adventure, a principle of curiosity, and most importantly, a principle of loveliness, which I’ll come back to later. And which always has an eye on the question: how can we change the world, just a little bit, for the better?

I’m going to talk through a couple of things I’ve helped make for Coney. And my answer to the question – how does this impact on me, the artist? – should become clear.

A Small Town Anywhere. This is a piece of interactive theatre Coney first presented 5 years ago. 30-ish audience don hats to become the citizens of a small town, and recreate the most momentous week in the town’s history. You take an occupation – you might be Annie Le Priest, or Matt La Journaliste. It’s a little bit French. You wear a hat to signify your occupation but your character is you. You might meet in advance the Historian to the Town and he’ll cast you as your occupation and – as this is a town that thrives on gossip – ask you if there is a skeleton in your closet, a filthy secret. And this might fuel some of the gossip in the town. You might have your own ambitions – perhaps you want to become Le Mayor, or to expose the scandal behind Le Priest, or to marry your sweetheart, or something else you choose for yourself. And gossiping might help you towards those ambitions. You might gossip in conversation but there is also a working postal service, where letters are posted at the end of each day (which is about 15 minutes) and then ready to collect the next morning (5 minutes later). And there are two tribes in the town, the Wrens small-towners till they die, who have lived there forever – perhaps like yourself, Le Priest – and the Larks, a little more liberal flighty types – perhaps like yourself, La Journaliste – who have recently moved from the Big Country. You can tell which is which by the feathers in their hats.

So this is your town, and it’s just all of you. There are no other actors in the room. There is no hidden audience. Except for us behind the walls, stirring events behind the scenes. You’re guided by the voice of an unseen Town Crier, the news and the clock. And you might get letters from the Historian in the post reminding you Le Priest that today is the day you give the sermon in the town on morality, so an event might happen. Now one of you audience is secretly acting as The Raven, who knows all the secrets and is writing anonymous poison-pen letters to wreak mayhem. But also there is political unrest. The uneasy coalition between Wrens and Larks in the Big Country Government collapses on Thursday evening and one side takes power – which side? The vocal majority. But it’s an extreme faction, taking absolute power, and on Friday morning there comes a messenger from the new State – this town is now say a Wren town. Only the Wren feathers can be worn in the hats, the others removed or else. And the next day, another message, this town is an immoral town – we know this from the gossip – and must be cleansed. One person must be scapegoated and their body hung from the trees, otherwise tomorrow the army marching on your town will have no mercy.

So this is all created by us. This is the fiction, the world we have made. We have created this framework, hosted this space and given it over to you, our guests for the night, for you to play. And now we are responding entirely to the choices and actions you the audience make, individually and collectively. It’s completely different every night because it’s all of you in there, your play, your stories, your choices. And the best of these feel like gifts back to us. The moments which are surprising and delightful and silly and joyous. Or here at the crunch, where the Town must choose either to kill one of their own, or face destruction – can there be an act of heroism so inspiring that it will turn the Army to topple the government? Is there a stubborn voice which says ‘it doesn’t have to be this way’.

Here are some which I remember 5 years on, which made me literally put my fist in my mouth behind the scenes to stop myself from screaming ‘I can’t believe this is happening’.

The Town where Le Mayor, a softly-spoken man with a stammer, talked down a lynch mob who wanted to scapegoat him by saying: you can kill me but I want to save you from what it will mean for you to carry this out.

The Town where the shy Le Baker who’d been gleefully playing the Raven suddenly confessed, threw herself on the mercy of the Town. Who blinked and said: well you may be the Raven, but you’re our Raven. And they can get tae fuck.

Or The Town – where the elders for the night were a group of pensioners playing with our more usual 20-something audience – where the very hunky 20-something Le Woodcutter suddenly went down on one knee and proposed to the 70-something La Belle Chanteuse. She gigglingly accepted. Until her real-life daughter pointed out she already had a ring on her finger, so that she was forced to turn him down and break his heart.

These are gifts I have been given.

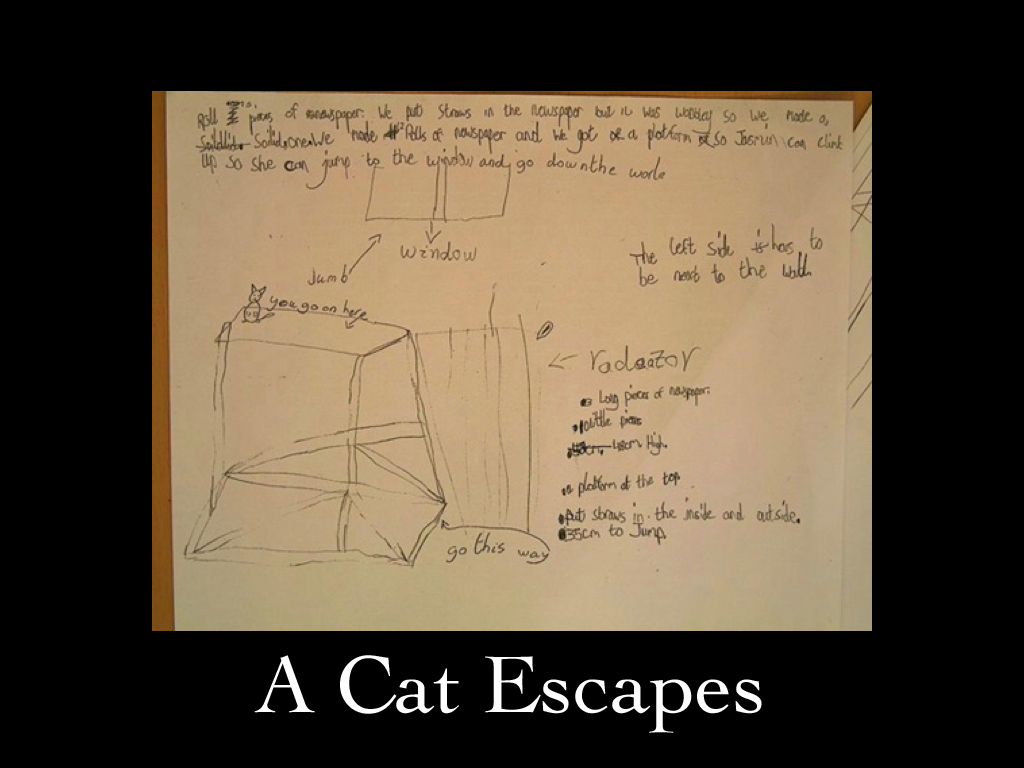

Here’s another. From an adventure in a classroom, A Cat Escapes, which I made with my fellow Coney Tom Bowtell, and developed with the help of primary school teacher Claire Lound. A class of 8-year-olds have had a book read to them in story time, Varjak Paw by SF Said, about a cat who learns an ancient feline martial art. One day they receive a parcel from Varjak, typewritten – because as we all know, cats can type – asking for their help in finding and rescuing his cousin Jasmine who has gone missing. To cut a long story short, they find an email address from which Jasmine responds. She’s been catnapped by Egyptologists. And now it’s like Prison Break for a cat, told in weekly episodes whenever Jasmine can get on the computer, where it’s up to the class to help. The first episode: there’s a small window in the room in which she’s held captive, too high to reach for such a small cat, but it might be the way out. Also in the room there is a pile of newspapers, a roll of sellotape, a random packet of drinking straws. What can she do? And so the class, guided by their teacher who’s playing along as if she has no idea what’s happening, are guided into a Keystone 2 lesson in design technology but a lesson with a heroic mission – can we build a tower structure out of these materials that will bear the weight of a small cat? And then turn them into instructions we can email her. So we can help her escape.

We’ve run A Cat Escapes many many times but this came from the first pilot, this set of plans created.

This is a gift to me. Specifically the care with which an 8-year-old has added a helpful picture of a cat on top of the tower with an arrow saying ‘you go on here’.

The principle of loveliness is about taking best care of people throughout the experiences from the very beginning when they first hear about it to the very end when they stop thinking and talking about it, about responding to people how they are and never presuming, about an open connection.

But it can also be represented by the act of making a gift to someone, to a stranger, in a way which is surprising and delightful for them to receive. A gift is good because it’s personal, but not so personal that it becomes creepy; exciting in its delivery but not so exciting it becomes freaky; a gift with value but no agenda, where the recipient never feels obliged to reciprocate.

And sometimes, in a way which I really can’t talk about publicly, these gifts for strangers happen – for real. Sometimes I’ve found myself involved in a gifting mission so improbable it starts to feel like an adventure – I’m thinking of one where I found myself tasked with getting a message to someone in a shop 11,000 miles away without being able to use phone or internet to contact them. In less than 20 minutes. I managed it, and 30 minutes later the recipient was tapped on the shoulder by a stranger who then handed him a parcel, the contents of which made him literally dance on the spot. My role in a mission like this is again a gift back to me with an impact at least as big as for the recipient. When the act of making a gift becomes a gift in itself and the smallest gift can make ripples of loveliness for years for giver and recipient and everyone else who hears its story.

It’s this which keeps me going.

And this question, always.

How can we make the play we make feel like an exchange of good gifts between strangers?

Back to all posts