The Parent Trap: exploring trust in healthcare

Posted on November 28th, 2023

Late last year, Coney was commissioned by the Goethe-Institut in London to make a game about trust. Trust was the theme of that year’s Kultursymposium, a festival held by the Goethe-Institut in Weimar. We ended up presenting several short games based on our research in the context of the Kultursymposium, with a playtest at Now Play This Festival at Somerset House in London. Here, Coney maker Zoe Callow writes on her research-to-making process for one of the games – and her instructions for setting a parent trap – in the second of a trio of blogs about the project.

How can trust be built, or broken, in state healthcare and medicine?

This was the question we aimed to ask through the Trust Games, the series of mini-games that emerged from the Goethe Institute commission. As part of the project, I researched, created and facilitated a game for the series: The Parent Trap.

1. Gather intelligence and choose your target

I began with a hunt for instances of public distrust in state healthcare throughout history. From a range of examples, I zeroed in on anti-vax sentiment, from smallpox in the 1850s to Covid-19 in the last decade.

I began this research under the naïve assumption that anti-vaxxers were not like me, but an academic paper by Elena Conis on the politics of 1970s mothers turned my view on its head. The paper linked the rise of anti-vax sentiment with the rise of social movements such as feminism and environmentalism, questioning patriarchal authority.*

Learning that some anti-vaxxers might share my politics, I saw how these movements might contribute to creating a risk averse approach to vaccinations – particularly when you add in public judgement of mothers for their children’s wellbeing, and the ways in which women of colour have been failed by UK healthcare.

So I chose my target: mothers and parents with caring responsibilities. I decided every game player would take on this role.

2. Build the apparatus of the trap (upon realising that a trap is needed)

I wanted my ‘trap’ to push players into making difficult choices about which aspects of their child’s wellbeing to prioritise, and which sources of information were trustworthy. I came up with a few pieces of apparatus to do this.

Time-limited challenges: Simulate the work of parents and carers, through a series of themed tasks under time pressure. For example, ‘choose a dinner your child will agree to eat in 2 minutes’ or, ‘Design a World Book Day costume in 5 minutes.’

Multi-tasking mechanism: Now that the parents are really busy, give them an important decision to make! Present them with some information about the health risks of the smiley face potatoes they chose for dinner, and they must decide whether to cook them.

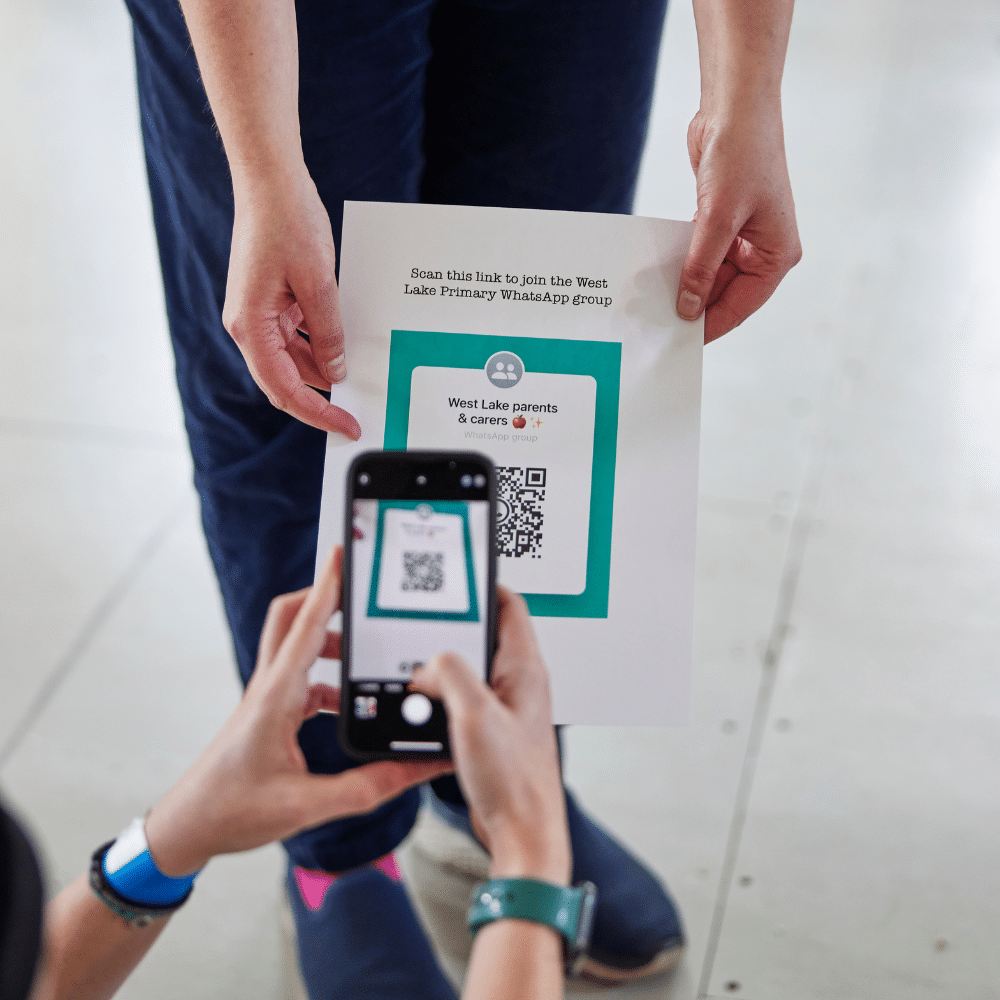

A WhatsApp subplot: Share most of the information about the health risks over a Parents & Carers WhatsApp group. Create an atmosphere of uncertainty, judgement and division through a pre-planned group chat narrative, where players can choose how much they read/engage/participate.

The challenge of this apparatus was creating a mechanic for winning the game which makes the challenges feel as important as the smiley face potato decision. The solution came in a final piece of apparatus from Tassos:

Public judgement: Tell the parents that they will be awarded ‘Parent Points’ for the challenges, which will be shared at the end of play. This incentivises a focus on the time-limited challenges and heightens awareness of public perception, making it more difficult to focus entirely on the dinner decisions.

3. Test the trap: evaluate its success

The challenge of playtesting was figuring out how to make it all happen live in a room full of people. Turns out, it’s not feasible to ask a room of 20 people to cook an actual dinner for a five-year-old!

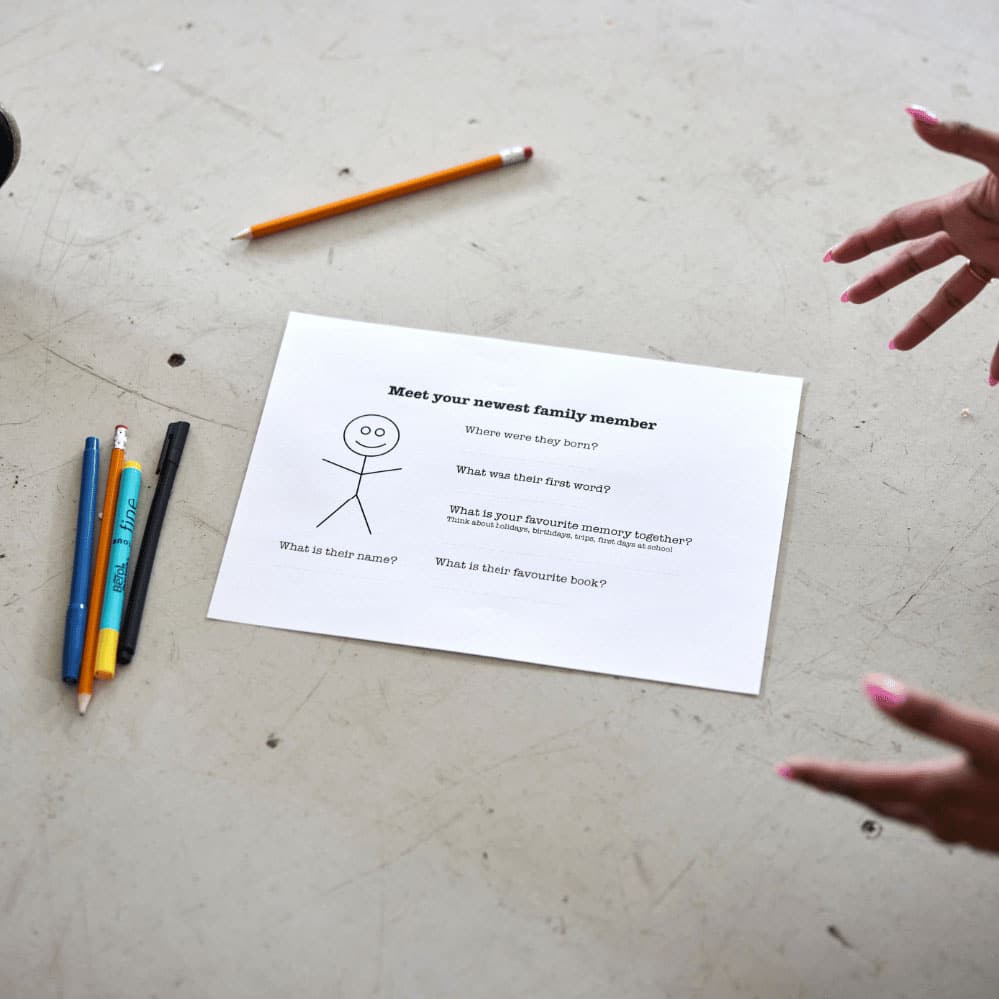

After exploring digital options, I arrived at a more lo-fi outcome. Players were grouped in ‘families’ and given an activity pack of challenges. Rather than actually cooking the dinner, they could circle their choices. This had the enjoyable side effect of paper and pens flying everywhere in each family’s hurry to complete the tasks.

On evaluating the trap overall, I was satisfied. Some players took a more risk-averse approach, losing points in the challenges by choosing to focus on the information about the health risks. Some also chose not to cook the smiley face potatoes, again losing huge numbers of points at the end of the game for disappointing their child. Other players decided to risk the smiley face potatoes for the sake of the Parent Points, but their victory felt superficial in the face of uncertainty about their child’s wellbeing.

There was no winning this game. The parent trap had worked!

As glad as I was that the game had caused these big feelings and realisations to come up, the speed of play didn’t allow for them to be processed fully. If I facilitated this again, I would want to explore building in more space for all of this to be explored and acknowledged, in the name of both audience care and impact.

*Source: Elena Conis, ‘A Mother’s Responsibility: Women, Medicine, and the Rise of Contemporary Vaccine Scepticism in the United States’, Bulletin on the History of Medicine (2013)