Playful Activism, game mechanics and participation

Posted on November 17th, 2022

Arts education researcher and friend of Coney Elvira Crois writes on Coney’s practice of social change through play.

Originally presented at iJADE Conference 2022 (The International Journal of Art & Design Education), ‘Belonging: Dialogues for culturally responsive art & design education’ online, 11 November 2022.

Unravelling Tacit Participation Strategies of Arts Education via Game Mechanics

by Elvira Crois (VUB) & Free De Backer (VUB)

Today, we want to tell you about playful activism

– playful activism as a type of arts education.

We will focus on the practice of a British theatre collective named Coney.

This theatre collective develops participatory and game-based work

and actively uses the term ‘playful activism’ to talk about some of their work.

By looking at their practice,

we unravel the ways in which they use game mechanics (or the mechanisms of game rules)

to incite a sense of agency in their participants

and how such sense of agency contributes to a sense of belonging.

–––

Playful activism is a specific type of creative activism.

It is activism that uses play as a tool to explore social change.

Not via playful messaging, but by inviting audiences to participate and play.

They devise activities that invite audiences to engage with

societal issues,

each other,

and their environment.

Playful activism brings together

(1) methodologies of play and

(2) expertise in participatory performance for the purpose of social change.

Thus, it is not simply about ‘playfulness’, which is an attitude

that refers to the infusion of characteristics of play into non-play activities (Sicart 2014, 22).

Such playfulness can, for example, be found in messaging developed through a playful approach or playful tactics in a protest.

Playful activism is about ‘play’, which is an activity

and refers to the actions performed within a game context.

Considering play as an activity,

playful activism refers to games and play settings that are used for activist purposes.

These can, for example, be participatory performances or arts educational workshops.

The term ‘playful activism’ is most notably used by the British theatre collective Coney. Both in their work with adults and children, they use strategies from participatory performance to allow audiences to explore themes ranging from climate change, such as their upcoming project with Greenpeace, to surrogacy, e.g. the game The Surrogacy Act (2021) (Mees 2011).

A recent addition to Coney’s repertoire is the Barbican Box, for which Coney collaborated with the Barbican to develop a remote arts educational intervention for schools.

The Barbican Box is a first good example

of how Coney uses game mechanics to activate participants.

ConeyxBarbicanBox 2021 from Coney HQ on Vimeo.

Game mechanics are the mechanisms of a game,

drawn up from the rules,

that make a variety of actions possible.

In a way, we could look

at the dynamics between rules and its game mechanisms and the actions of the participants

as the dynamics between strategy and tactics.

The strategy is the general game plan and the tactics are the mobile actions that move on, with, or against the general playfield of strategy. The play activities devised by Coney are systems, i.e. systems that set boundaries (or horizons of participation) that frame action, delineate action but also give rise to action. Their work invites participants to step into a play frame and probe their agency at this micro scale – their agency, which is the ability to take action, the ability to choose and the subsequent outcome of choice (Breel 2017).

As you have seen in the video,

the playful activism of Coney not only remains within the space of the workshop

but makes the connection with the outside world via ‘gifting’.

In other words, they make the connection between

the micro play world

and the societal world at large.

The participants are prompted to explore their local environment via a reconnaissance mission via which they get a sense of how

different people

and different ecologies

are connected to each other

and affect each other

and impact each other.

Then, using their mundane superpowers,

the players develop a gift for (someone of) their local community or school.

The players are awakened to possibilities beyond themselves

and learn how their agency – even on a micro level – can impact their surroundings.

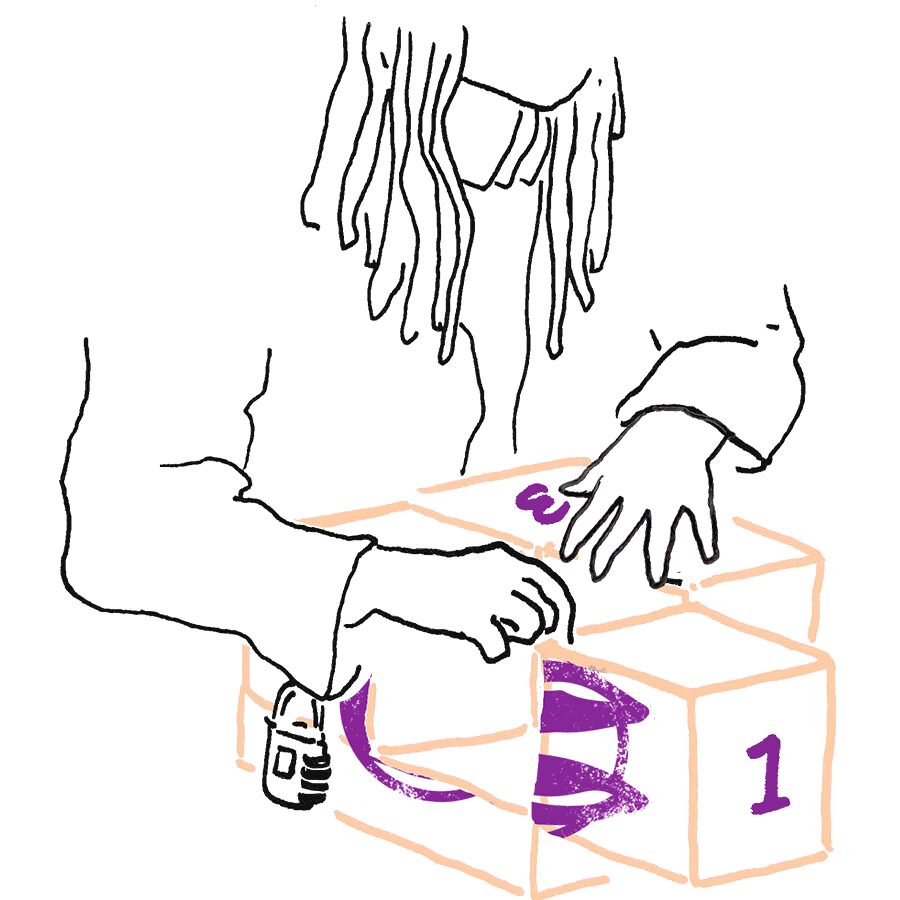

At an even more minute, nano scale,

Coney uses a simple game to awaken people’s agency via game mechanics.

This is present in the way, for example, Toby Peach – associate director of Coney –shows players of a game what it is to change game mechanics.

According to Toby,

when learning to change the world of a play space,

players are imbued with a sense of agency.

This can be explained by means of the game Roast the Aubergine.

In this game, the participants sit on chairs placed in a circle.

One person sits in the middle of the circle, on a stool.

The person in the middle is ‘the aubergine in the oven’.

The people sitting around are ‘the cooking team’.

The aim is to roast the aubergine (i.e. the person in the middle);

This is possible by heating up the oven to 200 degrees.

The cooking team heats up the oven by swapping seats.

The aubergine tries to get out of the oven

by trying to occupy an empty chair of the swapping participants.

If the aubergine succeeds in sitting on a chair in the circle,

they become part of the cooking team.

The person who lost their chair becomes the aubergine.

So, how do changing the game mechanics come into play here?

After playing a first round,

Toby would ask the players:

“What makes a game fun?

What makes this game fun?

Which rules are present that contribute to the fun?

Can we invent a new rule that possibly makes this game even more fun?”

He focuses on how the game mechanics impact

one’s experience

and the modes of conduct

between players.

Then, the players decide together on a new rule

and try the game with the new rule.

Such a new rule could be:

‘If one participant lifts their butt,

everyone of the cooking team needs to leave their chair

and find a new chair to sit on’.

This means that when someone from the cooking team accidently lifts their butt,

the aubergine has more chance to become part of the cooking team.

It could also mean that if someone from the cooking team wants to help the aubergine,

they could lift their butt intentionally.

After playing the game with the new rules,

Toby would ask the players again how they experienced the game

and what it means for the group dynamics to have different rules.

Thus, Toby makes explicit how – otherwise tacit – rules impact modes of conduct.

The participants are thus not only invited to develop their own tactics within the rules – such as making sure they have eye contact with another player before changing seats.

They are equally invited to reflect upon and create their own game mechanics.

Throughout the play activity,

players become familiar with the game mechanics of a frame,

with the possibilities it offers as well as its limits.

Via this process of getting acquainted,

players can absorb what makes sense to them,

imagine their own principles,

and apply the change they want to see.

Coney invites the participants to reclaim the frame as a space of possibility.

They offer a context for experiment

‘where one can practice at low risk,

where the pace can be slowed down,

and where iterations and variations of actions can be tried’

(Crois 2022).

By realising that they can play with the game mechanics,

the players learn about the ways in which such rules affect modes of conduct.

They learn about the impact.

They learn about agency,

i.e. agency within

– about the tactics they use

within the horizon of participation to win –

but also agency by moving the strategy

– about how their tactics can be embedded in the game mechanics and move the horizon of participation –

They also learn about ‘contributory justice’ (Mills et al. 2016),

which is about what a person is allowed to contribute or actually gets to do

and which recognizes that people who have a greater sense of agency

will contribute more easily to their surrounding world

(Breel 2017; Goessling et al. 2021; Ploof and Hochtritt 2018).

Thus, Coney supports agency by finding meaningful action within play and through play.

They focus on agency on the micro scale of the play world with the intention

to trigger the feeling within the players that they can replicate this in the outer World,

to trigger the feeling of agency in their own social setting,

to incite the possibility of contributory justice in their social setting,

and to improve their overall sense of belonging.

- Breel, Astrid. 2017. ‘Conducting Creative Agency; the Aesthetics and Ethics of Participatory Performance’. PhD thesis, Kent: University of Kent.

- Crois, Elvira. 2022. ‘Worldmaking: Crafting Cultures With and For Young People’. Online Assitej Magazine, 2022. https://magazine.assitejonline.org/2021-22/worldmaking-crafting-cultures-with-and-for-young-people/.

- Goessling, Kristen P., Dana E. Wright, Amanda Claudia Wager, and Marit Dewhurst. 2021. Engaging Youth in Critical Arts Pedagogies and Creative Research for Social Justice. New York: Routledge.

- Mees, Annette, ed. 2011. ‘Art Heist, 2010: An Interactive Adventure by Coney’. In Museums at Play: Games, Interaction and Learning, 84–94. Edinburgh: MuseumsEtc.

- Mills, Martin, Glenda McGregor, Aspa Baroutsis, Kitty Te Riele, and Debra Hayes. 2016. ‘Alternative Education and Social Justice: Considering Issues of Affective and Contributive Justice’. Critical Studies in Education 57 (1): 100–115.

- Ploof, John, and Lisa Hochtritt. 2018. ‘Practicing Social Justice Art Education: Reclaiming Our Agency Through Collective Curriculum’. Art Education 71 (1): 38–44.

- Sicart, Miguel. 2014. Play Matters. Playful Thinking. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Elvira Crois is a postdoctoral researcher in arts education at Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Their research focuses on aesthetics of audience participation, performer training, and participatory strategies for social change.

Free De Backer is Associate Professor in the Department of Educational Sciences at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Her research and teaching focus on arts and cultural education, and on participation in various learning environments at different ages.

Back to all posts